The energy drink market has exploded in the past decade with products such as Redbull, Rockstar, Monsters, etc. Interestingly, these beverages are often consumed under the pretense that they will help your performance in the gym. Energy drinks are the highest reported “supplement” taken by college athletes.

These beverages often contain carbohydrates, B vitamins, caffeine, and taurine. While there is ample research showing that carbohydrates or caffeine alone increase exercise duration and capacity, relatively little is known about the effect of these caffeine and carbohydrate based energy drinks on performance.

Also, if you have ever pulled an all-nighter in college and slammed back a few of these in one sitting you know they can have some “interesting” effects on your heart. The cardiovascular effects of these energy drinks during exercise has not been documented.

Well, good thing there are geeks like Dr. Mike T. Nelson out there to answer these questions for us.

Cardiovascular and ride time-to-exhaustion effects of an energy drink

Dr. Mike and his colleagues recruited 15 participants to determine whether a popular energy drink (Monster) would improve time-to-exhaustion in recreationally active young adults and whether it would affect their cardiovascular function

The Subjects

15 recreationally active (8 males and 7 females) in their mid 20’s were rectruited to perform the study. They were healthy with a mean BMI of 25, mean body fat of 22% and had an average peak oxygen uptake of about 40 ml/kg/min

Testing Acclimation

One of the things about peak aerobic capacity testing and time-to-exhaustion testing is that they are kind of weird tests and there is definitely a “learning curve”. Often times participants will do really poorly during the first test and then substantially better on their second just due to their familiarity on the second test.

To prevent any issues of the participants doing substantially better during their actual tests, they were acclimated to the test during three preliminary visits (1 peak aerobic capacity test and 2 ride time-to-exhaustion tests).

The Nutrition Intervention.

“The study utilized a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover design. Subjects were randomized for preexercise intake with the energy drink (ED) or placebo and received the opposite treatment a minimum of 7 days later (see Table 1 in the paper for ingredients).

Regular version Monster ED was standardized at 2.0 mg per kilogram of body mass (mg · kgBM-1) of caffeine and the placebo was prepared from non-caffeinated diet Mountain Dew and lemon juice by a lab staff member. Both drinks were served in a dark, opaque container and consumed 60 minutes before testing started.

The beverage was consumed within a 10-minute period from the time it was received”*.

Exercise Testing

For both the ED and placebo the participants performed a peak aerobic capacity test (explained more thoroughly in the paper) and a ride time-time-to-exhaustion test.

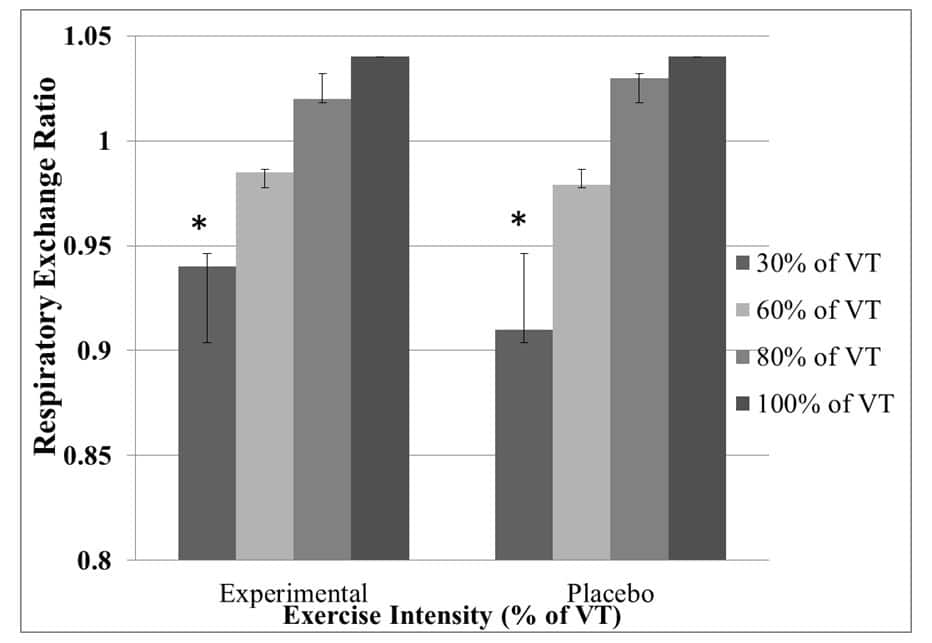

Metabolic data was also collected so we can look at how the ED influence substrate (i.e. carbohydrate and fat) metabolism.

Heart Rate Variability

Beat-by-beat heart rate (HR) data was collected using LEAD II ECG and heart rate variability (HRV) analyzed for each participant

The Data

Heart Rate

Not surprisingly, the ED caused an increase in resting heart rate from about 58 beats per minute to about 65 beats per minute.

The ED did not have a significant effect on HRV though. I wonder what long-term consumption would do to HRV

Do Energy Drinks Increase Performance?

According to this study, the answer is no. The ED did not improve the time-to-exhaustion.

There was a decrease in RER at low intensities when the participants consumed an ED, suggesting more glucose utilization at lower exercise intensities.

The Wrap Up

ED are marketed to give you more energy and improve your workouts. If your workouts involve any sort of aerobic capacity or time to exhaustion type of work you can put down the ED, as it is probably not doing you any good.

*Cited directly from the paper