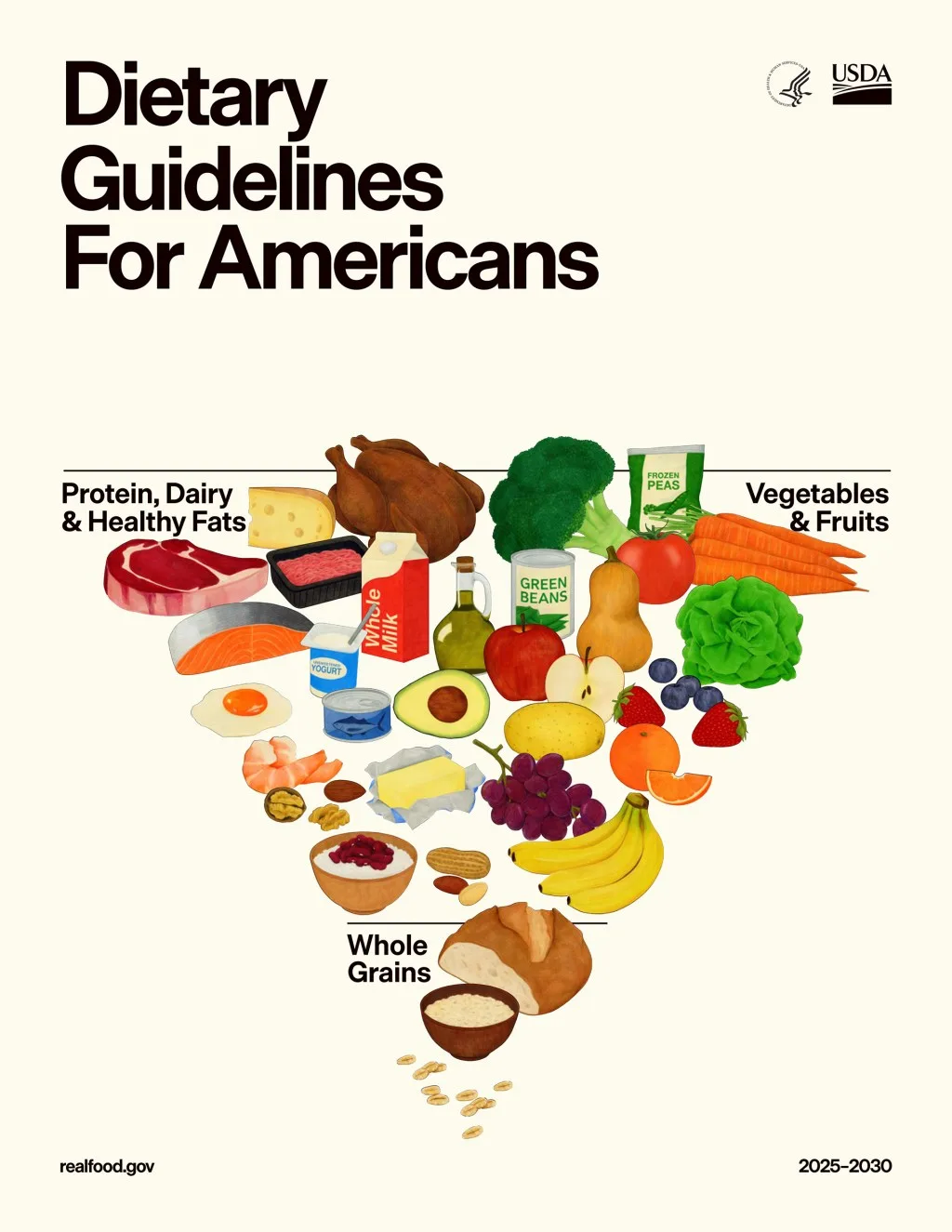

This week, a new food pyramid was announced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as part of updated federal nutrition guidance, detailed in the official USDA and HHS announcement. And, as anything related to nutrition tends to do, it immediately caused a significant amount of noise across the internet.

Normally, I do not spend much time writing or offering commentary on guideline updates like this. But given the response to it, this felt like a good opportunity to provide some context and practical insight that may actually be useful.

Before we debate whether these new recommendations are good, bad, or somewhere in between, we need to level set on something important.

Jump to a Topic

The Reality of Food Guidelines and Human Behavior

The first question we should ask is not whether the new food pyramid is “right,” but whether food guidelines meaningfully influence how people eat.

At the population level, the answer is clear.

They do not.

Regardless of whether you liked or disliked previous versions of the food pyramid or food plate, most people did not follow them. And they still do not. This is not a judgment, just an observation backed by decades of data.

Looking at the previous iteration of dietary guidelines, estimates vary slightly depending on methodology, but the numbers consistently fall into these ranges:

- Roughly 80–90 percent of US adults do not meet fruit intake recommendations

- Around 90–99 percent do not meet vegetable intake recommendations

- About two thirds exceed recommended saturated fat intake

- Approximately 90 percent exceed recommended discretionary or empty calories

This matters because it frames the entire discussion. Food guidelines rarely change population behavior, especially when environmental, social, and economic pressures dominate food choices.

Keep that in mind as we move through the new food pyramid guidelines.

The New Food Pyramid: What Has Changed

Like most nutrition frameworks, the updated food pyramid includes elements that are genuinely helpful and others that deserve closer scrutiny. The reality is not binary.

Let’s walk through the major components.

Protein Recommendations in the New Food Pyramid

The updated protein guidance is one of the more meaningful changes and generally moves in a better direction.

Recommending protein intakes in the range of approximately 0.54 to 0.73 grams per pound of body weight is, for most people, a significant improvement over the long-standing RDA of 0.8 grams per kilogram.

That said, there is nuance here. For individuals in higher BMI categories, those targets may need adjustment. Protein recommendations are not one-size-fits-all.

Where the guidelines become less helpful is in the language used to justify the recommendation. The statement that “the war on protein is over” adds unnecessary hyperbole. There has never been a war on protein, and framing nutrition in combative terms does not help people make better decisions.

The more reasonable takeaway is this: most meals containing high-quality, nutrient-dense protein from animal and plant sources is generally good advice. Saying that every single meal must prioritize protein is probably overstated, but the overall direction is sound.

Full-Fat Dairy: Is the New Guidance Justified?

The updated stance on full-fat dairy will likely raise eyebrows, but it is not without support from the literature when viewed in context.

Research comparing low-fat and full-fat dairy shows mixed results. More recent data suggest that full-fat dairy consumption does not meaningfully contribute to obesity or cardiometabolic disease when overall dietary patterns are considered.

Across meta-analyses and randomized trials, full-fat dairy intake is associated with inverse, neutral, or sometimes positive relationships with cardiometabolic outcomes, depending on the population and dietary context.

Interestingly, studies that show negative outcomes for full-fat dairy often find inverse relationships when total dairy intake is considered. When dairy is broken down by type, such as milk, cheese, yogurt, and butter, the results remain mixed.

The most practical takeaway is this: the fat content of dairy is rarely the primary driver of health outcomes. For most people, choosing low-fat versus full-fat dairy is not the deciding factor between good and poor nutrition unless it meaningfully alters total calorie intake.

Fruits and Vegetables Remain the Foundation

This section is not controversial, nor should it be.

Virtually every nutrition study ever conducted shows that people who eat more fruits and vegetables tend to weigh less, live longer, and experience better overall health.

The new food pyramid reinforces this point, which is appropriate, even if adherence remains low.

The guidance emphasizes eating fruits and vegetables in their whole, minimally processed form. That advice makes sense in many cases. Whole fruits provide fiber, water, and satiety that juices and dried fruits often lack.

However, the emphasis on freshness can be misleading. Frozen fruits and vegetables typically retain comparable nutrient and fiber content and are often more affordable and easier to store. From a practical standpoint, frozen produce can be just as valuable as fresh.

Grains in the Updated Food Pyramid

The guidance around grains is one of the least contentious aspects of the new food pyramid.

Encouraging whole grains while reducing refined carbohydrate intake is broadly supported by evidence. Suggesting fiber-rich options and reducing highly processed grain products aligns with both calorie control and overall nutrient intake.

Recommending two to four servings per day is generally consistent with the carbohydrate and fiber needs of most people, depending on energy expenditure and dietary context.

Fat Intake and Saturated Fat Clarification

Much of the online discussion surrounding the new food pyramid and fats is based on misinterpretation rather than what the guidelines actually state.

The updated guidance explicitly reaffirms limiting saturated fat intake to less than 10 percent of total calories and replacing it with unsaturated fats, particularly polyunsaturated fats.

This recommendation aligns with the existing body of randomized and observational research aimed at reducing cardiovascular disease risk at the population level.

The idea that the new food pyramid encourages higher saturated fat intake is not supported by the text of the guidelines.

Processed Foods: Context Still Matters

Processed foods are a permanent feature of modern food systems. Avoiding them entirely at a population level is unrealistic.

The evidence consistently shows that diets high in processed foods lead to higher daily calorie intake, particularly among individuals who do not track intake. This is one of the strongest and most consistent findings in nutrition research.

However, diets that include small to moderate amounts of processed foods, while maintaining energy balance and an overall nutrient-dense dietary pattern, tend to carry minimal long-term risk.

Much of the social media discussion around processed food ingredients ignores the bulk of scientific evidence. Topics like seed oils are often discussed without meaningful engagement with the data. In most cases, those discussions are not worth your attention.

What the New Food Pyramid Really Means

Food guidelines matter conceptually, but their real-world impact on behavior is limited. Environmental constraints, social norms, and economic factors play a far larger role in shaping how people eat.

The new food pyramid does not represent a dramatic departure from previous guidance. The main differences include slightly higher protein targets, fewer grains, and continued emphasis on fruits and vegetables.

If someone consistently met their protein targets and consumed five to six servings of fruits and vegetables per day, their health and body composition would likely improve. That was true before this update and remains true now.

Will the new food pyramid meaningfully change consumer behavior? Almost certainly not.

Will it measurably improve population-level health outcomes? Probably not in any detectable way.

Should you spend significant time worrying about a new diagram used to represent dietary guidance? No.

Focus on what happens in your own household. That is where nutrition decisions actually matter.

Try our nutrition coaching, for free!

Be the next success story. Over 30,000 have trusted Macros Inc to transform their health.

Simply fill out the form below to start your 14-day risk-free journey. Let's achieve your goals together!