We’ve pretty much seen it all. Any scenario you can imagine related to diets and weight loss we have encountered. And one of the most frequent errors we see people make (and most common questions we get) is related to people eating back their exercise calories. Now this error is so common because of how a lot of current wearable technology and food logging software works.

If you wear an Apple Watch you will see that your exercise will increase your total estimated calorie expenditure. If you log your food using MyFitnessPal you will undoubtedly see that your total daily calorie “allotment” is adjusted up to compensate for those exercise calories. In this article we are going to talk about why eating back your calorie may be holding you back from results… and why SOME people should, but you probably shouldn’t.

Jump to a Topic

Should You Eat Back Your Exercise Calories

How Calculate Calorie Estimates Are Calculated

The total calories you need on a daily basis are usually estimated using scientifically tested and verified Estimating Equations. These equations have been developed based on data from hundreds of thousands of people from across the world and are generally within ~10% of being accurate for most people.

For the purposes of this article it is important to understand how most of these calculators/equations work, including the calculators we use on our website and our food tracking app.

In almost all cases these calculators have two steps:

- They estimate your basal metabolic rate (BMR) based on your age, height, weight, and biological sex.

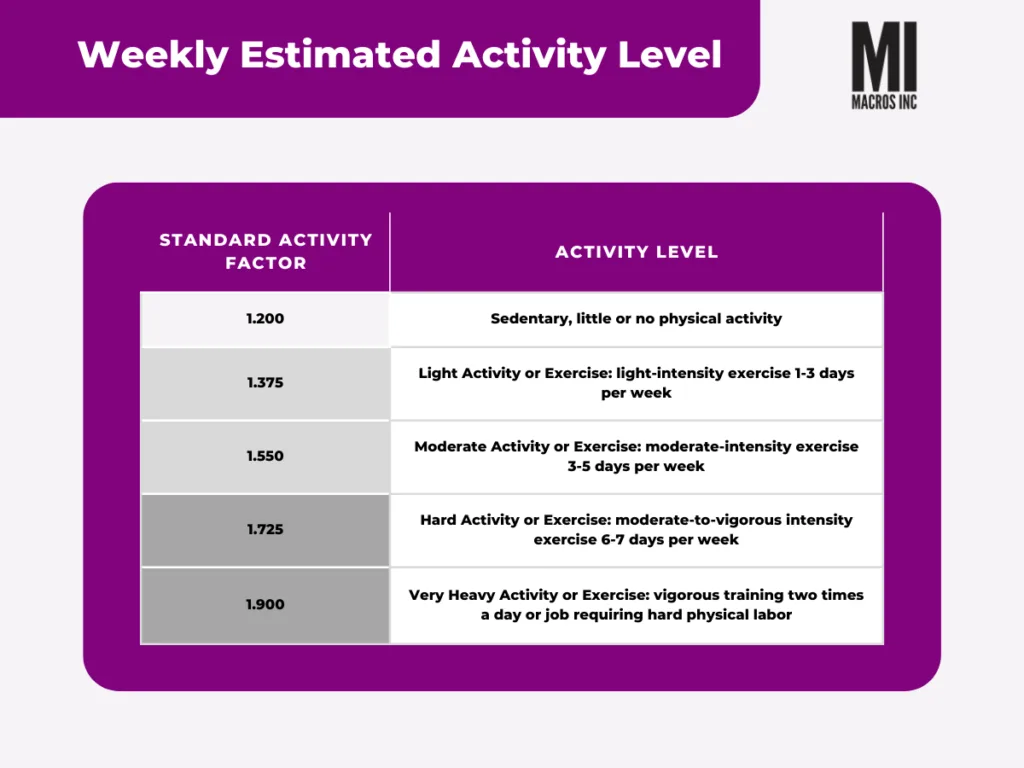

- They adjust your BMR based on your weekly estimated activity level.

It is incredibly helpful if we use an example here. Let’s assume we have the average American female who is 5’4”, 170 pounds, and 50 years old who exercises ~2-3 days a week and has a moderately active job. For this, we would probably use the Harris-Benedict equation.

Step 1

In step 1 we would use the female equation which is:

BMR = 655.1 + (9.563 × weight in kg) + (1.850 × height in cm) – (4.676 × age)

We just plug in our information and we get

BMR = 655.1 + (9.563 × 77.3) + (1.850 × 162.5) – (4.676 × 45)

BMR = 1484

Step 2

In step 2 we would adjust for her physical activity level which is considered lightly active.

- Total Energy Expenditure = BMR * Physical Activity Level

- Total Energy Expenditure = 1484 * 1.375

- Total Energy Expenditure = 2,040 kcals

This means that when we utilize calorie calculators to estimate our calorie expenditure, our exercise and physical activity is already included in these estimations. As such, when we consider including our exercise activity on top of what is already estimated we will be substantially overestimating our true calorie expenditure in a given day.

This is in fact what happens in almost all cases when people attempt to “eat back” their exercise calories – they are adjusting for an adjustment that was made at baseline.

Calorie Trackers Are Notoriously Inaccurate

Based on what we just learned, it turns out that for most people, calorie calculators already “bake in” our exercise and physical activity habits into our calorie estimations from scientifically verified estimating equations. In addition to this, it turns out that most commercially available fitness trackers are wildly inaccurate.

Before I tell you exactly how inaccurate they are, let’s talk about how these devices estimate exercise-specific energy expenditure. Although it can be a bit complicated, the truth is that all fitness trackers effectively use a combination of heart rate and step count to estimate expenditure. And these devices have meaningful error rates for those two things, which means that the end measurement (calorie expenditure) will also be wrong.

Apple watches can have up to a 9% error rate on heart rate.

Garmin has been reported to have a similar error rate with upwards of 11% error.

So if the primary variable for how the estimated exercise-specific energy expenditure is calculated is not super accurate, how far off is the calorie estimate for exercise? Well, it turns out that depending on the device, it can be off by upwards of 95%.

That is not a typo. This effectively means that data is almost completely useless.

In other studies it has been reported that these devices are wrong more often than not… regardless of device. Also, to make matters worse, it is not like they always overestimate or underestimate. They are all over the map.

They just are horrible for estimating energy expenditure from exercise.

I wish this were not the case. Our jobs would be SO. MUCH. EASIER. if they were indeed accurate.

So, taking this back to our food intake.

If we were to try and eat back the calories our watch said he burned… we would be trying to eat back a number that is wrong almost every single day.

That is a recipe for failure.

Who Should Eat Back Exercise Calories

I think at this point it is pretty clear that for most people trying to eat back exercise makes almost no sense.

That being said, there are some people who should consider eating back exercise calories: athletes and people with non-regular, unusually high energy expenditures.

In the case of athletes, they often have fairly regular training and exercise schedules and have either tracked their workout volume closely or used much more reliable measures of energy expenditure and can have a much more accurate estimate of how many extra calories they might burn from longer or higher volume training sessions. In these cases, it would be smart to increase calorie intake to offset a non-intentional calorie deficit.

Another case where eating back exercise calories makes sense is if you have an unusually high energy expenditure and weight loss is not your primary goal. For example, if you went on a very long multi-day hike, ran an ultra-marathon, or spent the entire weekend doing very heavy manual labor. During periods of non-regular, unusually high energy expenditure it may make sense to increase calorie intake to offset the unintentional deficit.

Summary

In most cases, eating back exercise calories is not a winning strategy, especially if your goal is weight loss. Most calorie calculators already include your estimated physical activity, which means it is not necessary to adjust for slight daily variations in exercise induced calorie expenditure. Additionally, most commercial fitness trackers (e.g., Apple Watch, Garmin, FitBit) are so inaccurate they are basically useless for estimating exercise-specific calorie expenditure. It is far more effective to eat consistently, track your body weight over time, and adjust your weekly calorie averages based on your rate of progress.

Try our nutrition coaching, for free!

Be the next success story. Over 30,000 have trusted Macros Inc to transform their health.

Simply fill out the form below to start your 14-day risk-free journey. Let's achieve your goals together!