Fire up the barbecue, buy some meat and call your friends over. The topic of protein intake has been confusing people for too long and this is the end of it.

People all over the world just want to know: “What do I need to eat to live a long, high-quality life, and look good doing it?”

A Google search for “how much protein” brings up over 71 million results. Many with differing opinions. Some professionals try to make the case that we are consuming way too much protein. Some say high protein diets put us at risk of osteoporosis and loss of kidney function.

While all this information is well-intentioned, it is not well-informed. Research shows many health benefits with protein intakes higher than the current recommended daily allowance (RDA).

So it’s time to set aside preconceived beliefs and set the facts straight with 8 things you need to know about protein.

What is Protein

In its simplest form, protein is a complex molecule made up of amino acids. These amino acids are the building blocks of protein and are essential for various bodily functions. From forming enzymes and hormones to building and repairing tissues, protein is involved in nearly every aspect of our body’s functioning.

What Protein Does in the Body

Protein serves numerous functions in the body, including promoting muscle growth, supporting immune function, aiding in digestion, and acting as a source of energy when carbohydrates and fats are insufficient. Understanding these functions highlights the importance of consuming adequate protein in our diet.

Protein and Muscle Growth

One of the primary roles of protein is in muscle growth and repair. When we engage in physical activities such as resistance training, our muscles experience tiny tears. Protein helps repair these tears, leading to muscle growth and improved strength. Athletes and individuals involved in regular exercise often have higher protein requirements.

Complete vs Incomplete Proteins

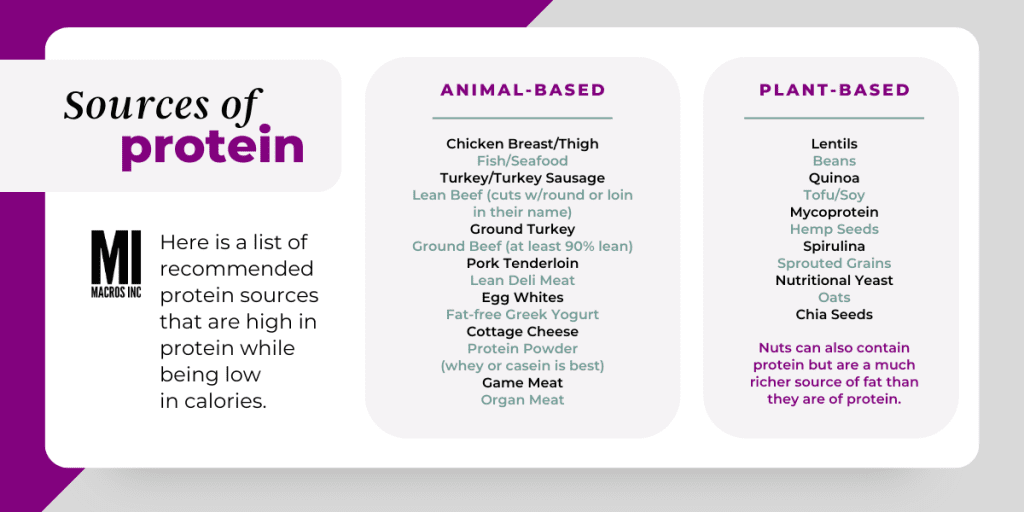

Protein sources are classified as either complete or incomplete. Complete proteins contain all essential amino acids necessary for our body, such as those found in animal products like meat, eggs, and dairy. Incomplete proteins lack one or more essential amino acids, commonly found in plant-based sources like legumes, grains, and nuts. Combining different incomplete protein sources can create a complete protein profile.

Protein Timing

While total daily protein intake is crucial, the timing of protein consumption can also impact its effectiveness. Consuming protein-rich foods or supplements within the post-workout window is particularly beneficial for muscle recovery and growth. Spreading protein intake evenly throughout the day ensures a steady supply for the body’s needs.

Protein Quality

Protein quality refers to how well our body can utilize the amino acids in a particular protein source. Animal-based proteins are generally considered high-quality due to their complete amino acid profiles and high digestibility. However, by combining different plant-based protein sources, we can improve the overall protein quality.

Protein Requirements: RDA vs Individual Needs

Some confusion on protein requirements stems from not understanding the dietary guidelines and how they apply to individual needs. The RDA (Recommended Dietary Allowance) is set by The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institutes of Medicine to help guide dietary choices. You’ve probably seen the RDA shown as a percentage on food labels.

The RDA is the minimum level of intake required for health needed to avoid a deficiency. It doesn’t account for your athletic or aesthetic goals. The current RDA for protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of bodyweight. But those looking to improve performance, build muscle or recover from injury would benefit from consuming more.

Benefits of Eating More Protein

Several studies have looked at the effects of high-protein diets on body composition. These studies consistently showed that high-protein diets lead to greater weight loss, fat loss, and maintenance of lean body mass (Phillips et al., 2016).

When combined with resistance training, a diet higher in protein is even more effective at increasing muscle mass and reducing fat. For example, Longland et al. (2016) compared a diet containing 2.4 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight to a diet containing 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight and found that the higher protein diet had better results.

In addition to its effects on body composition, a higher protein intake also increases calorie burning and helps control hunger. Johnston et al. (2002) conducted a study with two groups of females. One group consumed a high protein diet with 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight, while the other group consumed the same number of calories but less protein as recommended by the Food Guide Pyramid. The higher protein group showed an increase in energy expenditure of up to 90 calories in a 24-hour period.

Common Concerns

Despite common concerns, eating more protein does not negatively affect kidney function in individuals with healthy kidneys. The Institute of Medicine concluded that the protein content of the diet is not responsible for the decline in kidney function with age (Phillips et al., 2016).

Similarly, the idea that high protein diets cause osteoporosis is not supported by evidence. Research has shown that higher protein intakes actually improve bone health and are associated with lower hip fracture rates when calcium levels are adequate (Fenton et al., 2011). Therefore, promoting an alkaline diet to prevent calcium loss is not justified.

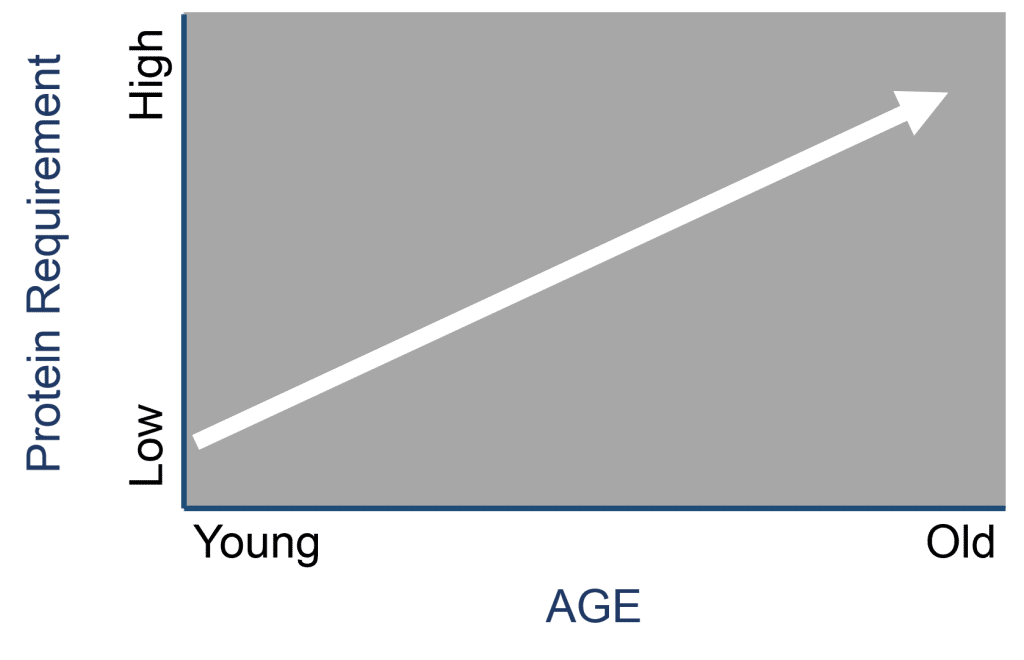

Protein Needs to Increase with Age

But let’s start to think beyond looking and feeling good right now. About how we want our lives to be 20, 30, even 30 years from now. The maintenance of a high-quality life as we age is our ability to stay independent. And that comes down to having enough strength to do basic daily tasks.

A major health challenge as we get older is the slow decline of muscle mass and strength. And low protein intake contributes to it (Phillips et al., 2006).

The strength and muscle mass you build right now goes into a savings account that you can draw from as you get older.

And things don’t get easier as we age. We need more exercise and more protein to get the same muscular adaptations as when we’re younger. Moore et al. (2015) showed older men are less sensitive to protein intake than younger men. They need a greater relative protein intake per meal to maximally stimulate protein synthesis in the muscle (31 grams vs. 19 grams).

Consuming a diet high in protein is one of the best ways to improve your body composition and stay strong as you age. If you’re healthy, a high protein diet will not have negative consequences.

But if you’re still worried, well, that means more protein for the rest of us.

References