One of the most interesting ideas recently put forth in nutrition is this idea of the “thrifty” gene. Essentially, what this idea relates to is that humans evolved in a time where we lived in periods of feast and famine, and as such, our bodies adopted mechanisms such that we can become thrifty, and store extra energy that comes in to hold for times of famine.

This concept suggests that in some people, dieting results in less weight loss and that periods of overeating lead to more weight gain than in others. The popular media has morphed this idea in something along the lines of the following, “some people can’t lose weight when dieting because they have a thrifty gene”.

There has been substantial research into this topic over the last few years and a few recent studies have helped us really understand this idea. Normally, an article like this would start with a full definition of ‘thriftiness.’

However, I want to introduce the general concept of two ideas first and explain thriftiness in detail at the end, as it will make more sense then.

Thriftiness can be defined as a set of adaptations (or lack of adaptations) that the body goes through to minimize weight loss during periods of restriction and to maximize storage during periods of excess.

Spendthrift can be defined as a set of adaptations (or lack of adaptations) that the body goes through to maximize weight loss during periods of restriction and to minimize storage during periods of excess.

Can Thriftiness Explain Poor Weight Loss?

Have you ever noticed that many people go on diets, but they do not all see the same result? My guess is you have. While much of that is explained by lack of adherence, poor reporting, and a lot of other factors, there is some evidence that even with proper food adherence, people may lose weight at different rates.

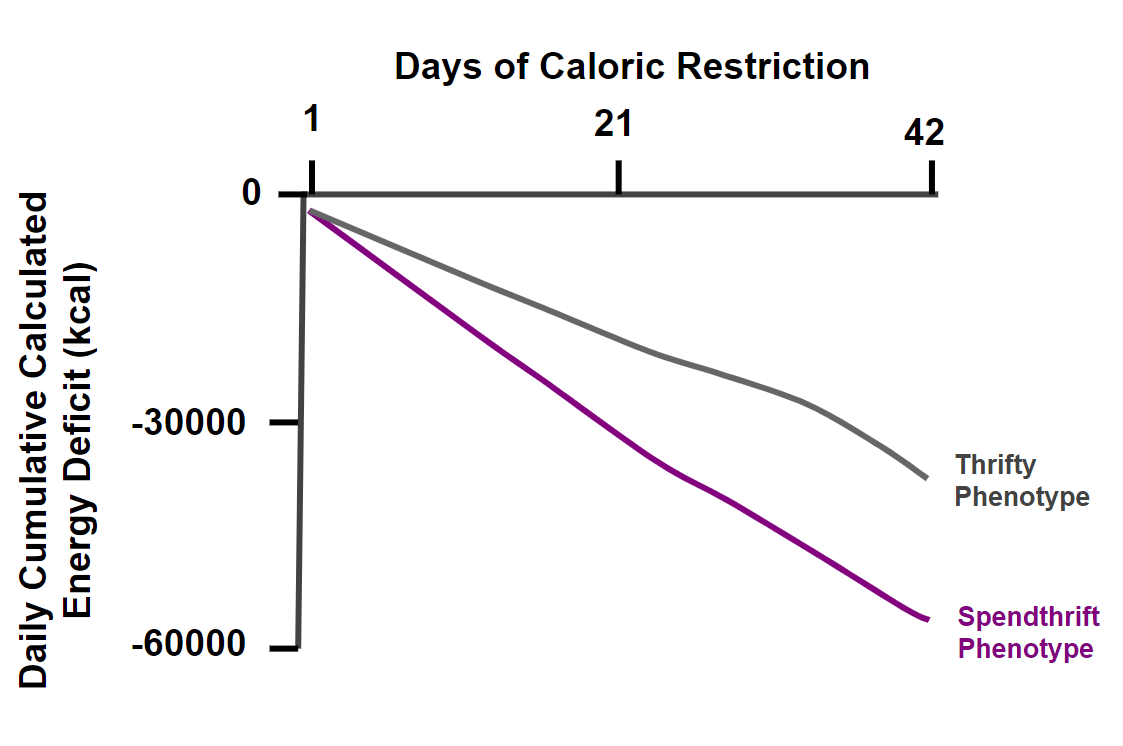

In support of this idea we go back a few years to a study that was done that tracked people during periods of dieting (i.e. calorie deficits) and examined the rate and amount of weight loss. This study found that during periods of caloric deficits some people reduce their energy expenditure more than others in adaptation to consuming fewer calories (more on this later). These adaptations lead to different amounts of weight loss during periods of dieting. Ultimately, the findings from this study suggested that people may indeed fall into two different categories: 1) thrifty ,or 2) spendthrift.

While the above was the primary finding from this study, some of the secondary findings from the study were quite illuminating:

First, the researchers did two short experiments in which they took people and had them fast for a full day and tracked their energy expenditure, and then they overfed them by 200% of their daily calorie intake and also tracked their expenditure. During these studies, they found that people had a wide range of adaptations to either underfeeding or overfeeding.

Second, the study examined what factors helped explain the differences in the energy deficit and daily energy expenditure. The researchers found that how sedentary a person was each day, and how they responded to the underfeeding or overfeeding 24 experiment noted above, explained a large amount of the differences between the two “types” of people. Essentially, how people responded to a 24 “feast or famine” situation helped explain how well they did with weight loss. But the really interesting part was that the “response” was how much they changed their energy expenditure.

So the answer to the question of, “can thriftiness explain poor weight loss?” appears to be, yes, at least in part. How people adapt their expenditure to changes in energy intake explains at least some of why certain people lose more weight when dieting than other people do.

Can Thriftiness Explain Weight Gain?

Based on the findings above, thriftiness can help explain why some people lose more weight than others during similar periods of caloric restriction. Another key question here is does thriftiness relate to different rates of weight gain among people, especially after periods of dieting.

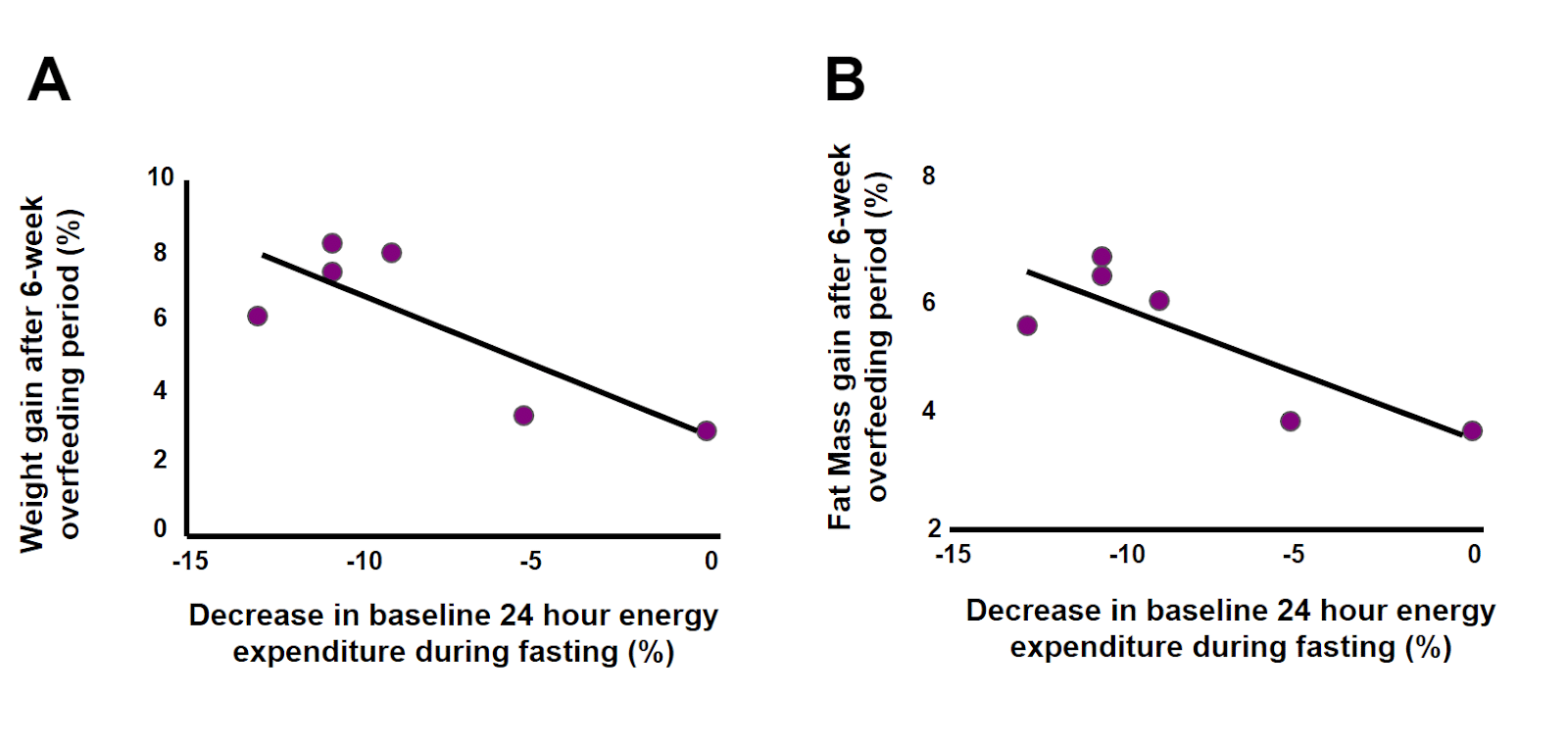

This idea was investigated recently in a paper published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. In this study, researchers took a group of 7 men and overfeed them for 42 days on a diet that consisted of roughly 50% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 20% protein, which is fairly similar to a standard American diet in terms of macronutrient ratios. At the start of the study they also subjected the participants to 24 hour fasting periods and 24 periods of overfeeding and tracked how they adapted to that.

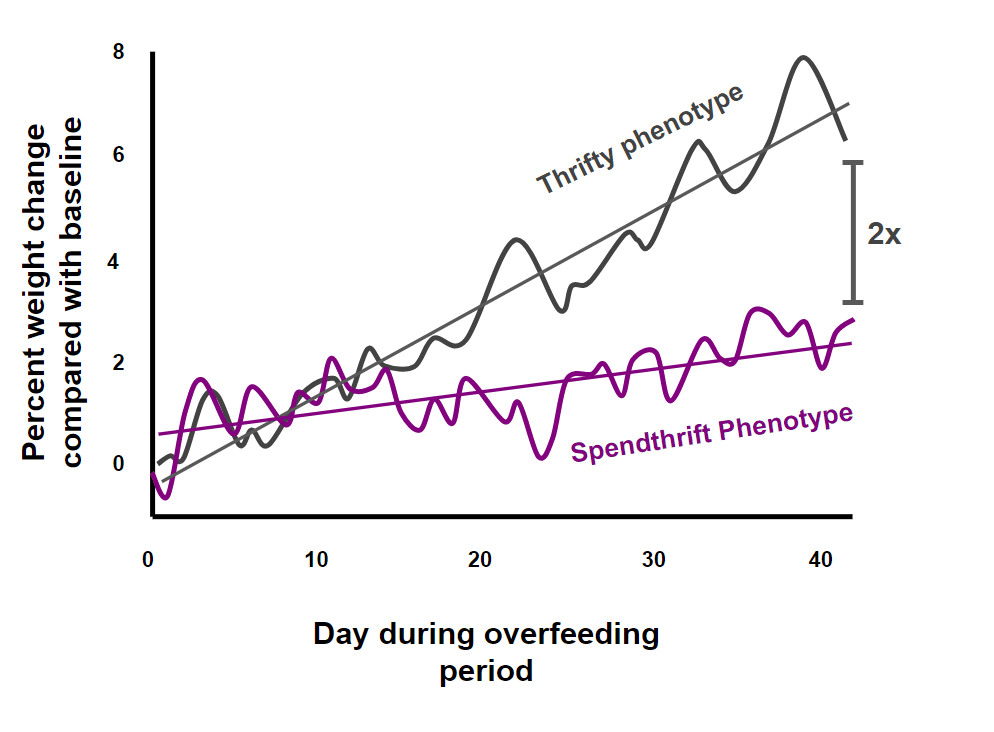

On average, each participant consumer about 50% more calories than their maintenance levels at baseline and gained about 6% total body weight (~4 kg) over the 42 days. However, there was a wide range of weight gain, with one individual gaining only 2.5% of total body weight and another gaining 80% of total body weight.

Similar to the weight loss study mentioned above, they found that the adaptations to energy expenditure that occurred during the 24 hour fasting test helped explain at least some of the differences between those people who gained a lot of weight compared to those who gain a small amount of weight; those who saw the biggest reduction in energy expenditure during the 24 hour fasting test gained the most weight during the 42 days of overfeeding.

Relationships between percentage change in 24EE during 200% overfeeding (A) and fasting (B) as assessed at baseline and metabolic adaptation as assessed at the post-overfeeding period.

One of the more interesting findings in this study was that there was a greater increase in daily energy expenditure than was predicted simply by body weight gain, suggesting that there are indeed some “defense” mechanisms present to defend against body weight gain during periods of overfeeding.

The findings from this study suggest that there may be different metabolic phenotypes, and that there may indeed be more “thrifty” phenotypes and more “spendthrift” phenotypes.

How Should We Think About “Metabolic Thriftiness”

At the start of this article I indicated I would talk a little bit more about what thriftiness is at the end of the article. I put it at the end because I wanted to cover the idea as a broad concept first and show that there does appear to be some level of “thriftiness” people have. Now we can talk a little more about what that might actually be. Here we go.

The idea of metabolic thriftiness comes with a lot of extra intellectual baggage that we can probably dispense of and get straight to the core of what it is, and what it is not.

The idea of their being a thrifty phenotype seems to be validated in the literature, but it does not appear to be a binary situation. Rather it appears on a spectrum from very thrifty to very spendthrift. People can fall anywhere in that spectrum, as far as I can tell from the data.

As far as we know, there is no true “thrifty gene”. Instead, the phenotype that manifests from the spectrum of phenotypes is polygenic (coming from many genes), and also likely has epigenetic and environmental factors. In truth, the thrifty phenotype is the sum of many different things, including different rates of thermogenesis from food, different hormonal adaptations to dieting, changes in physical activity, etc.

The other interesting aspect of many of these findings is that, while there is some hormonal and immutable factors that impact our adaptations to dieting and overfeeding, one of the largest levers we have is 100% under our own conscious control: physical activity. In the studies examining the thrifty phenotype, the amount of daily energy expenditure assigned to the inherent phenotype is fairly small.

Even if we over exaggerate the findings and say that it explains 150-200 calories per day, physical activity can be leveraged to amounts substantially higher than that. For example, in many overfeeding and/or underfeeding studies changes in daily physical activity often accounts for 200-400 calories per day.

When you place that into the context of dieting for people in the real world, that means that people can actually account for their inherent phenotype and overcome small differences with proper planning, especially through physical activity.

Summary

People lose and gain weight at different rates. Part of the difference between people appears to be due to how their body adapts to periods of caloric restriction and/or overfeeding.

The adaptations that occur are multifactorial, but can often be summarized into two different “phenotypes”: 1) the thrifty phenotype in which the sum of the adaptations cause people to lose less weight and gain more weight than others, 2) the spendthrift phenotype in which the sum of the adaptations cause people to lose more weight and gain less weight than others.

These adaptations are partly due to differences in diet induced thermogenesis, hormonal changes, and physical activity.

For all intents and purposes, there are aspects of this that are out of people’s control, but physical activity is something that can be a large lever that shifts people from their natural phenotype. For example, someone with a “thrifty” phenotype can lose the same amount of weight, or greater, than someone with a spendthrift phenotype if they consciously increase physical activity to compensate for adaptations.

Many people may think the point of this post is to identify the fact that some people lose weight and gain weight at different rates than other people. That is partly the purpose of this article, but not entirely. The major point is to highlight that yes, people respond differently in the magnitude of their response to dieting or weight gain, but largely, these differences can be understood and managed, primarily through addressing energy expenditure.