Bulking and cutting is a practice that has persisted in bodybuilding for the better part of a century. It is so ingrained into the sport and culture that it’s almost inevitable to have heard the term in some form or another if you’re a regular gymgoer or poked around on the internet.

Bulking has been around since the late 19th century, and is referenced by early bodybuilders such as Charles Atlas, Bernarr McFadden, Eugen Sandow, and Arthur Saxon. The initial definition of the term was simply putting on body mass. However, in bodybuilding, cutting more specifically refers to the act of eating in a caloric surplus to gain lean body mass.

Cutting is a relatively more recent practice. While the act of cutting weight for combat sports has been around for decades, this was typically done as a means to temporarily reduce bodyweight to fit into a weight class. As with bulking, cutting also has a more specific definition in bodybuilding: the act of eating in a caloric deficit to lose fat mass.

Bulking and cutting is a time-honored staple of bodybuilding and a common practice to this day. It remains one of the most efficient ways to increase muscle mass and lower body fat levels over time. However, there’s much more nuance to it than “eat a ton of food, then diet really hard.” There are a host of other considerations to keep in mind, and in this document, I aim to address them as completely as possible.

Let’s go!

Jump to a Topic

The Complete Guide to Bulking and Cutting

Why Bulk and Cut?

The goal with bulking and cutting is to gain net lean body mass while keeping body fat levels controlled. By separating the two goals into discrete phases, it is generally more time-efficient than pursuing both simultaneously. This is increasingly the case the more advanced a trainee is, i.e. the heavier they lift, the more lean mass they gain, and the more they lean out.

The one other option is a body recomposition (recomp). Here, the goal is to gain muscle and lose fat simultaneously. For new trainees, this is a perfectly viable option. However, the more advanced a trainee gets, the harder it becomes to pursue both goals simultaneously. The other value of a recomp-based approach is for maintenance, or keeping your body around its current metrics. This works well for people who are content with their current physique or resting between bulking and cutting phases.

Should I Bulk or Cut First?

This is a somewhat individual question, and there are few hard and fast rules about when to do one vs. the other. As a general rule, someone should start a bulk when they’re relatively lean and start a cut when they have too much fat to be comfortable with. These are very subjective goalposts, though. The way I like to look at it is to ask yourself if you’re comfortable adding 5-15 pounds of fat to your frame. If the answer is no, chances are you aren’t ready to bulk yet.

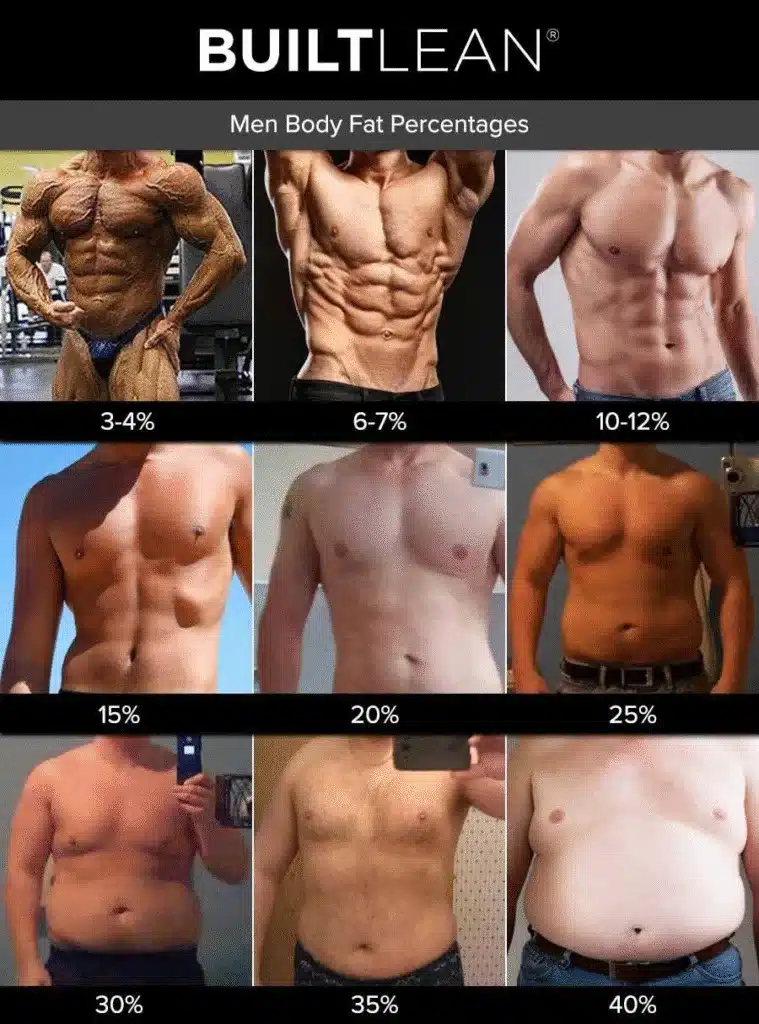

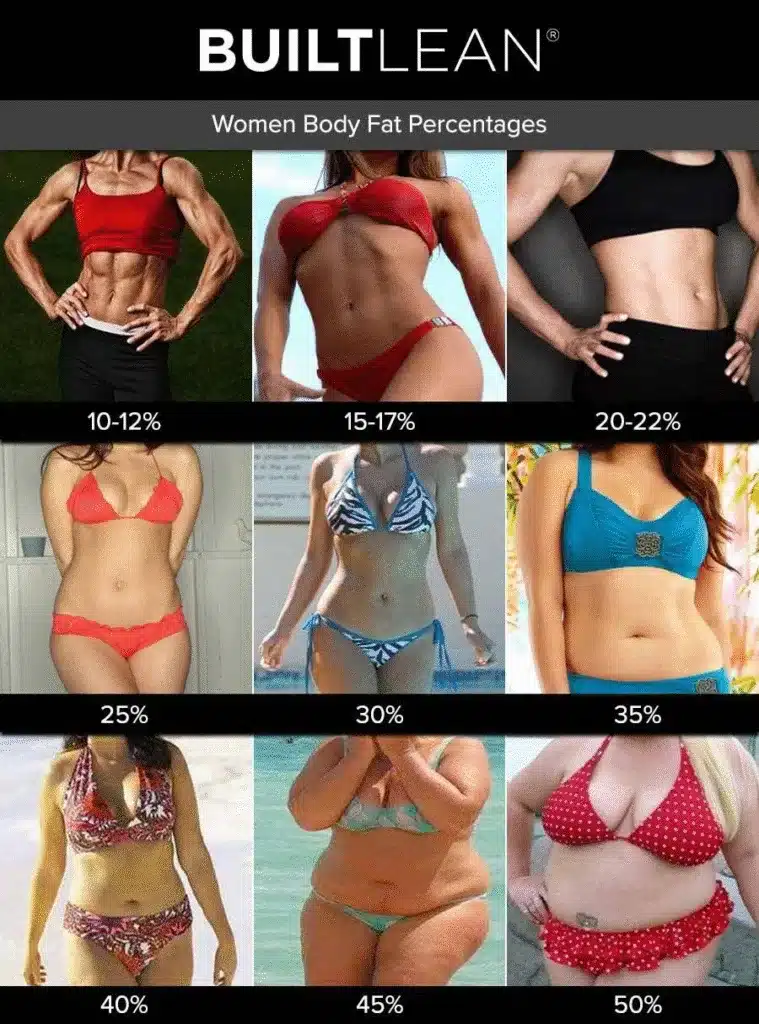

One other metric you can use is to set lower and upper limits to your body fat percentage. For most men, I would say somewhere around 10-12% as a lower limit, and 15% or so as an upper limit. For women, I would amend this range to 15-17% and 20%, respectively, as women naturally have a higher amount of body fat than men.

For most intents and purposes, visual estimates are perfectly fine for estimating body fat percentages. Assume most men start seeing some semblance of abdominal definition at around 15%, and having a six-pack at rest is usually around 10%. For women, these two values would be around 20% and 15%, respectively. (Figures 1,2)

There are two main reasons for setting a reasonable upper limit to your bulk cycle. First, keep in mind that the higher you end things on your bulk, the more ground you must cover when you diet back down on a cut. You generally want to spend as little time in a calorie deficit as possible, as it’s a period where growth is either severely limited or outright stalled.

The other reason for keeping body fat controlled comes from nutrient partitioning. In humans, there is something known as the p-ratio, which determines how incoming calories are partitioned between lean and fat mass. Body fat plays a significant role in hormone signaling, and the higher your body fat percentage gets, the more this ratio starts to skew toward body fat gain vs. lean mass gain. Thus, bulking is most efficient at lower body fat percentages.

However, note that calorie partitioning is a sliding scale, and not as simple as “the leaner the better.” At the lower end of body fat percentages, the body is also going to want to preferentially regain body fat. Also, there is no magic upper percentage where things transition to all fat, no muscle – it’s much less black and white than that. For more information on the p-ratio, check out these articles.

Expected Gains/Losses

When measuring this sort of thing, it’s best to weigh daily, first thing in the morning, on an empty gut and bladder. That tends to serve as the best baseline for accurate weight. From there, use either weekly or preferably monthly trends to gauge where things are headed. The reason for this is that bodyweight tends to fluctuate significantly from day to day and even week to week, so longer-term trends tend to smooth out a lot of the variation and give a clearer indication of overall progress. This is particularly true when accounting for variables such as the menstrual cycle.

Regarding bulking, muscle gain is generally a slow process, and it can take a considerable amount of time to really accumulate significant amounts of lean mass. For the average trainee, gaining approximately 1-2% bodyweight a month (.25-.5% per week) is a decent goal when bulking. Of those gains, approximately 50-75% will partition toward lean mass, and 25-50% will add on as fat mass. This usually approximates to around 2-3 pounds of lean mass and 1-2 pounds of fat mass gained per month. This ratio is dependent on several variables, including the genetics of the trainee, how advanced they are, their age, how aggressive their surplus is, and how efficiently they’re training.

On a cut, fat loss is also a gradual process, albeit a much faster one than gaining lean mass. For most folks, losing somewhere in the range of 2-8% bodyweight a month (0.5-2% per week) works well. This usually approximates to about 1-2 pounds of fat loss a week. The primary determinant of rates of fat loss will be the steepness of the calorie deficit. It is entirely possible to push for faster rates of fat loss with a lower calorie intake, but doing so comes with its own set of considerations and difficulties regarding training and food selection. Improper cutting can lead to losses in lean body mass alongside the lost fat mass, temporarily undoing the hard work of the previous bulk.

Duration and Timing

Duration

There aren’t really any hard and fast rules for how long a given bulk or cut phase should last. However, some factors will at least partially dictate how long a particular phase lasts. Arguably, the biggest pitfall with bulking and cutting is transitioning between the phases too often, i.e,. setting them to too short of duration. When planning your training cycles, it’s worth remembering that bulking and cutting work best when each phase is long enough to create measurable results—not just a few weeks here and there. This usually leads to not making significant progress in either direction, also commonly called “spinning your wheels.” This is a common scenario amongst trainees: starting a bulk, getting afraid of getting fat, ending it prematurely to cut, and ending back at square one all over again. When committing to a bulk or cut, make sure that it’s for the long haul.

Bulking

In a bulk, keep in mind that effective training is one of the major parts of success. I’ll address this later, but a core principle for muscle growth is progressive overload, i.e., increasing the amount of work a muscle does over time. It takes a significant amount of time to really get this going. Given that cutting tends to make progress much more difficult, it’s wise to push a bulk to milk strength and growth from the program as long as possible. Building off this, it’s not a bad idea to match the duration of a bulk to training cycles on a given program.

Additionally, muscle growth is a slow process. A trainee doing things well with training and nutrition may gain around 2 pounds (0.9kg) of lean mass per month in a surplus. Therefore, if they start a cut after only a month or two, they may only have a few pounds of lean mass to show for it. Given that ineffective cutting runs a risk of lean mass loss, the net mass gain may very well be insignificant, or even zero.

At a bare minimum, I would recommend a bulk phase last about 12 weeks, preferably longer. If a trainee begins their bulk at a low body fat percentage and controls their rate of gain, it’s not uncommon for bulks to last upwards of a year, especially early on. While the thought of gaining fat for such a long period of time can be worrisome, there are contingencies one can put in place to ensure things go smoothly (more on that below. For now, take the following saying: You have to gain fat on a bulk. You do not need to get fat on a bulk.

Cutting

The length of a cut is highly contingent on the results of the previous bulk. The overall goal is to get one’s body fat down to pre-bulk levels while retaining the lean mass that was built. On a typical bulk, one can expect about 1-2 pounds of fat gain per month. Since the typical cut runs at about 1-2 pounds of fat loss per week, that equates to about one month of cutting for every 2-4 months spent bulking.

It’s also worth noting here that cutting doesn’t necessarily have to be a straight, one-shot sort of deal. It’s actually a good idea to implement periodic diet breaks throughout the cut as needed. This serves a variety of physiological and psychological benefits that I’ll cover further on.

Additionally, successful cuts tend to be done in several stretches rather than one extended period. It’s not a bad idea to intersperse a cut with periodic diet breaks or refeeds to keep progress coming along smoothly and prevent burnout.

Finally, when transitioning between bulks and cuts, it can be useful to spend a couple of weeks at maintenance calories to let the body normalize a bit and prepare for the next phase of the diet. When moving from a bulk to a cut, this can help prep for the upcoming deficit. When moving from a cut to a bulk, this gives the body time to recover from the deficit.

Timing

While bulks and cuts can be set for any time of the year, there are certain times of the year when certain dietary goals are easier than others. For the typical trainee starting out, this is a non-issue – their primary goal is usually fat loss, regardless of the date. For someone who has achieved their target leanness, though, they have a lot more options available to them.

There’s an old mainstay that says that one should generally bulk during the winter and cut during the summer. In the winter months, clothing tends to be bulkier, more covering, and generally less form-fitting, so not being at your desired leanness isn’t quite as much of a mental game. Additionally, most of the holidays where folks are enjoying good food and treats tend to come around the end of the year, so if there’s going to be plenty of hearty eating, it might as well be put to good use.

Conversely, the warmer months tend to be when people want to wear shorts, swimsuits, or just show more skin in general. With that in mind, timing one’s dieting to begin sometime before or during the summer usually works out well.

There are other considerations here as well. For example, some people know that certain times of the year are going to be packed for them for social events, e.g. many birthdays in a row, annual trips or vacations, etc. In these cases, the timing of when to bulk, cut, or take breaks from either becomes a lot more individual.

Finally, people tend to get a little freaked out about timing the start of their cut “just right” so that they arrive at summer looking their leanest. The sentiment is understandable, but this can be a bit counterproductive for overall long-term gains. As long as there are set upper limits on when to stop gaining, a trainee will never be “fluffy” enough to really worry about their appearance. This is due to both that upper limit still looking “fit,” and having that ceiling be low enough that you’re never too far away from one’s target leanness. This is also a big part of why it’s preferential to start at a lean base to work from when beginning. Once that reference is known, it’s a lot easier to know what you’ll be working back toward.

An Example of a Bulk/Cut Cycle

Let’s say a hypothetical male decides to begin bulking and cutting. He’s currently at about 150 pounds body weight, 135 pounds (68.2kg) of lean mass, 15 pounds of fat, 10% body fat. He’s new to weight training and starting a dedicated progressive overload-based training routine.

He first goes on a nine-month bulking phase, eating in a surplus, gaining approximately 3 pounds per month, or 27 pounds. Of these 27 pounds, let’s say he gains 15 pounds of lean body mass and 12 pounds of fat. He ends his bulk at about 177 pounds body weight, 150 pounds of lean mass, 27 pounds of fat, 15.2% body fat.

Now, he wants to cut to finish off his first bulk/cut cycle by dieting back down to 10% bodyfat. He enters a caloric deficit, losing approximately 4 pounds a month. After three months, he’s down to about 165 pounds, 148 pounds of lean mass, 17 pounds of fat, 10% bodyfat.

As a net total after his first year, this trainee has gained 15 net pounds of lean body mass, while keeping his body fat percentage fluctuating between ten and 15 percent (Table 1). From here, he can either choose to maintain for a while or begin another bulk/cut phase.

| METRIC | INITIAL STATS | END OF BULK #1 | END OF BULK #2 |

| Body Weight | 150lb (68.2kg) | 177lb (80.5kg) | 165lb (75kg) |

| Lean Body Mass | 150lb (68.2kg) | 150lb (68.2kg) | 148lb (67.3kg) |

| Fat Mass | 15lb (6.8kg) | 27lb (12.3kg) | 17lb (7.7kg) |

| Body Fat Percentage | 10% | 15.2% | 10% |

| Net Change from Initial (Bodyweight) | 0 | +27lb (12.3kg) | +15lb (6.8kg) |

| Net Change from Initial (Lean Body Mass) | 0 | +15lb (6.8kg) | +13lb (5.9kg) |

| Net Change from Initial (Bodyfat Percentage) | 0 | +5.2% | 0 |

The Phases: Detail

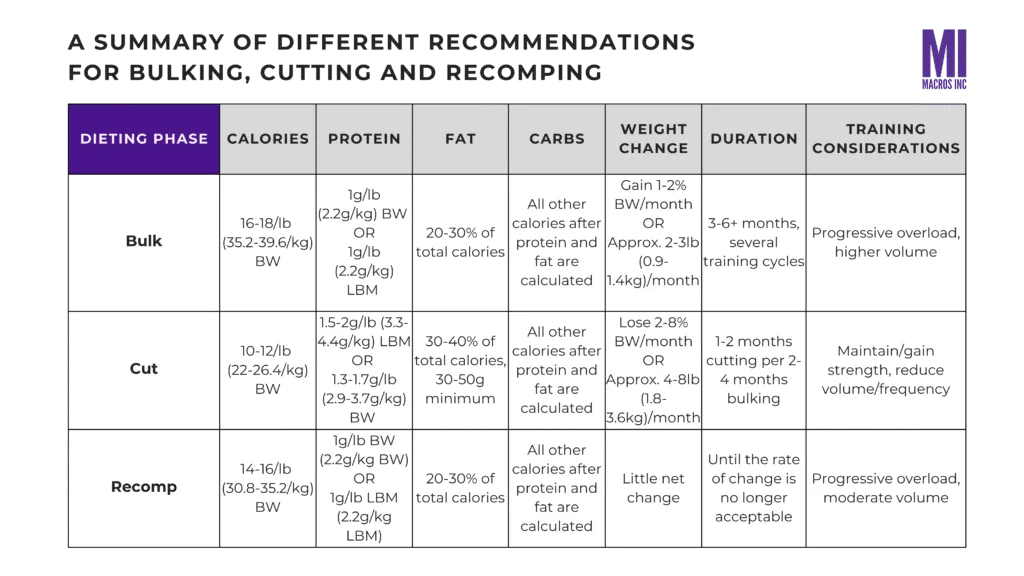

Now, it’s time to outline the three different phases: bulking, cutting, and recomping. For each section, I’ll break things down into two different categories:

Diet

In this section, I’ll talk about calories, macros, how to calculate them, and why they’re set the way they are. With the calories, all the estimates will be calculated using bodyweight multipliers. This isn’t an exact approach, but it tends to be significantly easier than most other equations out there, e.g. Harris-Benedict, Mifflin-St Jeor, and Katch-McArdle. These approximations should land you in the right ballpark, but regardless, you’ll have to adjust your actual values based on results.

Additionally, there are two different ways to calculate protein needs: One by total bodyweight and one by lean mass (total weight – fat weight). The latter approach is technically more accurate but requires calculation of body fat percentage to do so. This can be done with the visual estimates in the previous section, by calipers, etc. Once you have it, the two equations to determine lean body mass are as follows:

- (Bodyfat percentage / 100) = Bodyfat percentage in decimals

- (Bodyweight x bodyfat percentage in decimals) – bodyweight = Total lean body mass

Going by total bodyweight is also a fair metric, particularly if a trainee is already relatively lean. The higher in body fat percentage someone is, the more likely that estimating protein needs by bodyweight will overshoot the target. That said, there’s nothing inherently wrong with overdoing it on protein. There are other physiological needs for protein in the body besides skeletal muscle, and there are generally no health risks for high protein intake.

Training

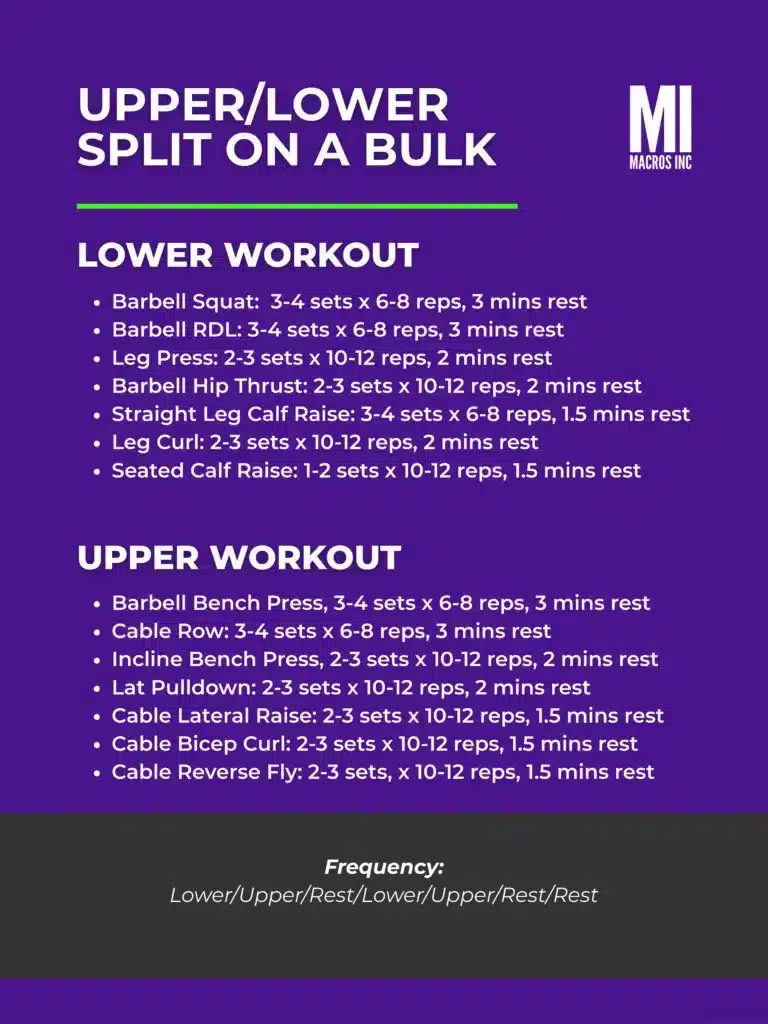

Here, I’ll discuss specific considerations regarding how to adjust training for each phase. I’ll also provide a sample workout for each phase of the diet. The setup will be a typical upper/lower routine, with an upper and lower day. The typical schedule for such a routine throughout the seven days of the week is Lower/Upper/Rest/Lower/Upper/Rest/Rest. Additionally, the written form of each exercise is as follows:

- (Exercise), (Sets x Reps), (Rest in Minutes)

- Reps = Repetitions. How many times to perform the exercise before resting.

- Sets = Groups of reps, i.e. how many grouped reps to do before moving on to the next exercise.

- Rest = How long to recover between sets. These should be full rest, or at most walking around. They are not used for another exercise.

I want to make clear that all of this is in the context of bodybuilding. Strength-focused athletes, powerlifters, and advanced lifters likely already have their own routines to follow. As such, I will also make general recommendations to consider when running through each phase of the diet.

Bulking

Diet

The typical person will usually start with calories in the range of about 16-18 per pound (35.2-39.6 kilograms) of bodyweight (BW) for a bulk. Alternatively, if maintenance calories are known, adding 10-20% to that should put calories close to the ideal target for bulking.

For protein, the typical recommendation is 1g/lb (2.2g/kg) of bodyweight. Realistically, the target value will be closer to 1g/lb ((2.2g/kg) of lean body mass (LBM). If the trainee is relatively lean (approximately 15% or less for men, 20% or less for women), the difference between 1/lb LBM and 1g/lb. BW should be fairly close.

For fat, typical values range between 20-30% of total calories, as the literature usually uses fat values in proportion to the total energy intake, not in grams per pound or kilogram. There is no strict physiological requirement for fat aside from the essential fatty acids, so one’s fat intake is usually preference-based (i.e. higher fats/lower carbs, lower fats/higher carbs). As a lower limit, I usually set it somewhere around 50g, if only to give some dietary wiggle room. For the essential fatty acids, a daily dosage of about 2-3g combined EPA+DHA is a good target.

Carbs will constitute most of the incoming calories on a bulk. Essentially, every calorie that hasn’t been assigned to protein or fat is distributed to carbs. These provide an important source of readily available energy and additional calories, helping to fuel workouts and make it easier to stay in a calorie surplus.

Training

Resistance training is a vital part of bulking, as it ensures that the calories are partitioned toward lean mass gain as much as possible. Muscle tissue requires three things to grow: adequate energy, sufficient amino acids, and a stimulus. The energy requirement is satisfied via the calorie surplus, the amino acids are provided by dietary protein, and the stimulus comes from resistance training. In particular, the resistance training must introduce increasing levels of stimulus for the muscle to work against. This is a concept known as progressive overload.

In practice, what this means is that a trainee must work increasingly harder over time to continue to promote muscle growth. This involves increasing one or more of three different training variables: intensity, frequency, and volume. Intensity generally refers to the magnitude of the stimulus itself. In weight training, this is most easily achieved via adding weight to the bar, cable stack, etc. Volume refers to the number of sets and reps performed for a given muscle group. Finally, frequency is how many times per week a given muscle group is trained.

Of these three factors, intensity tends to be the most feasible to improve over the long run. There are diminishing returns for increasing volume, and frequency is limited by recovery. Both of these are also restricted by feasibility, as many folks aren’t going to want to spend hours in the gym almost every day of the week. So once volume and frequency are set, the primary focus is on intensity.

For volume and frequency, there are many different ways to split this up, but based on research, somewhere around 6-8 sets or 40-70 reps per muscle group per workout, 2-3 times a week, tends to encompass the majority of requirements. These recommendations leave a significant amount of wiggle room for how things are laid out.In a bulk, the main difference compared to the other diet phases is work capacity. In a calorie surplus, energy levels and overall propensity for improvement are at their highest. As such, this is the prime time to get on a program, push progressive overload hard, and make as much improvement as possible. There are many programs that fit the bill, but here is an adapted upper/lower split as an example (Table 2).

Cutting

Diet

For most, cutting calories is usually set somewhere around 10-12 cal/lb (22-26.4cal/kg). Alternatively, if maintenance is known, shaving 10-20% of calories from that value should also put things at a decent starting point.

Protein needs on a cut are significantly higher than they are on a bulk. This is due not just to added requirements for lean mass, but also because the body takes some of the incoming protein as a source of energy. Here, an intake of about 1.5-2g/lb (3.3-4.4g/kg) lean body mass covers almost all possible needs. It very well may be that this is a bit overkill, especially in novice trainees, but, if we’re looking to minimize the possibility of muscle loss, it’s likely better to overdo it than come up short. Higher protein intakes also promote satiety, and other tissues besides skeletal muscle require protein, so there are other benefits to a high intake besides lean mass retention.

Again, calculating protein needs based on body weight is a possible alternative, but contingent on the leanness of the trainee. The higher the body fat percentage, the more that total bodyweight is going to overestimate one’s protein needs. If a trainee is relatively lean, the above LBM recommendations equate to roughly 1.3-1.7g/lb (2.9-3.7g/kg) bodyweight.

Conversely, dietary fat tends to be more restricted on a cut due to the reduction in calories as a whole. As before, there is no strict requirement for dietary fat, but extremely low fat intake can be conducive to hormonal troubles. Somewhere around 30-40% of total energy intake is usually a fair spot, or about 30-50g of total dietary fat. Again, the priority here is essential fatty acids, at a combined intake of about 2-3g of EPA+DHA.

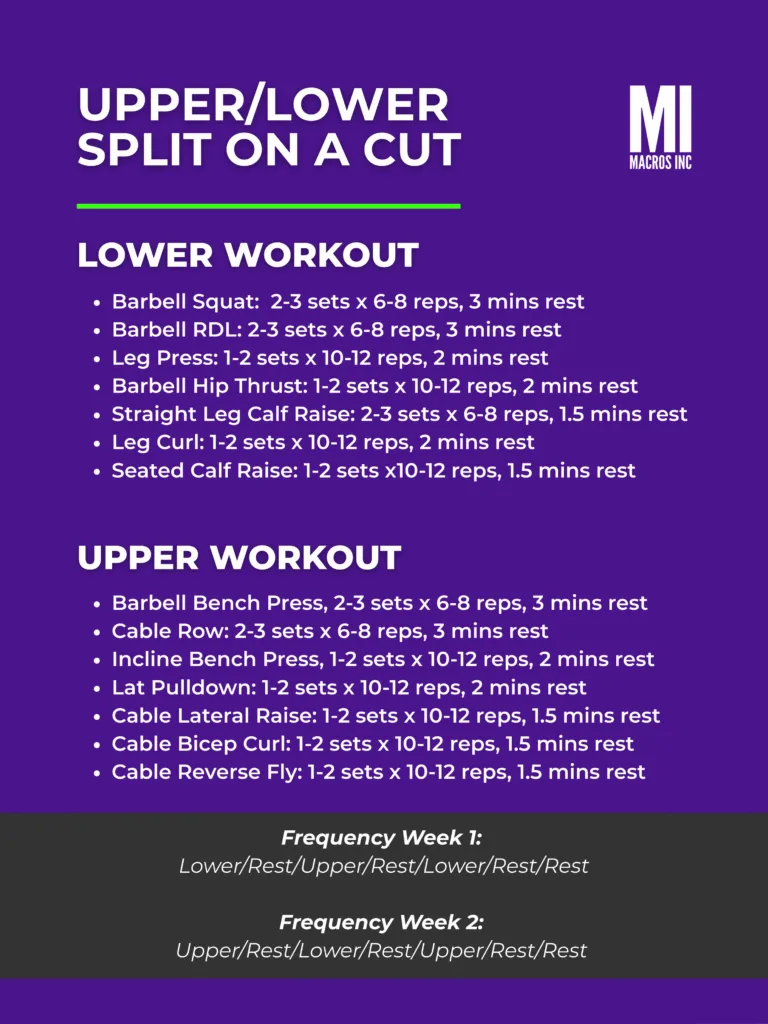

Training

Hypothetically, the same program used for bulking should also be adequate for cutting. The main difference is that work capacity is no longer a given due to energy restriction. It becomes increasingly difficult to make progress on a cut or even to maintain one’s current progress. Something generally must be compromised.

Going back to the three variables, the one most closely associated with lean mass retention is intensity. Volume and/or frequency can be scaled back as necessary to accommodate one’s impaired recovery. In fact, as long as intensity, i.e. weight on the bar, is maintained, both volume and frequency can be scaled back by up to about two-thirds without risking lean mass loss. What this plays out as is that the number of workouts per week and work sets can be decreased as long as you continue to lift around the same weight. Additionally, the more aggressive the calorie deficit is, the more volume and frequency should be scaled back to compensate.

Since intensity has to be maintained or increased during a cut, things such as deloads have to be accounted for. The best place to set a deload is during a diet break, where calories are brought back up to maintenance levels. This is the prime time to lower the intensity without risking lean mass loss.

If we return to our setup for bulking, we could modify it for a cut rather easily (Table 3).

Recomping

Diet

Recomping can be seen as somewhere between bulking and cutting, and generally not difficult to set up compared to the other two. Still, bulking and cutting remain the go-to strategies for trainees who want faster, more dramatic results, while recomping is better suited for slower, steady progress.

Calories are typically set around 14-16/lb (30.8-35.2/kg) bodyweight. Since energy is still not a limiting factor, protein and fat intakes can be kept around bulking values. Carbohydrate intake is generally reduced from what it is on a bulk, simply because calories are reduced.

Training

Training-wise, recomps are like bulking. The goal is progressive overload, increasing work over time. The main difference is that work capacity is less on a recomp than a bulk due to the lack of a calorie surplus. This also tends to be the main reason why progress slows faster on a recomp than a bulk. For most intents and purposes, the workout scheme between the two is equal, although it may be useful to reduce volume or frequency slightly to better accommodate progression.

Summary

Here is a summary of all of the information given for all three phases of the diets (Table 4).

Conclusion

The bulking and cutting process seems intimidating at first glance, but when broken down piecewise, it’s a lot easier to digest. In most cases, bulking and cutting are also not strictly necessary for progress, especially early on. However, if done correctly, the bulking and cutting process is a dietary tool for potentially gaining muscle and losing fat in an efficient manner. The only way to know if it’s for you or not is to give it a try.

Now go get eating and lifting!

Try our nutrition coaching, for free!

Be the next success story. Over 30,000 have trusted Macros Inc to transform their health.

Simply fill out the form below to start your 14-day risk-free journey. Let's achieve your goals together!